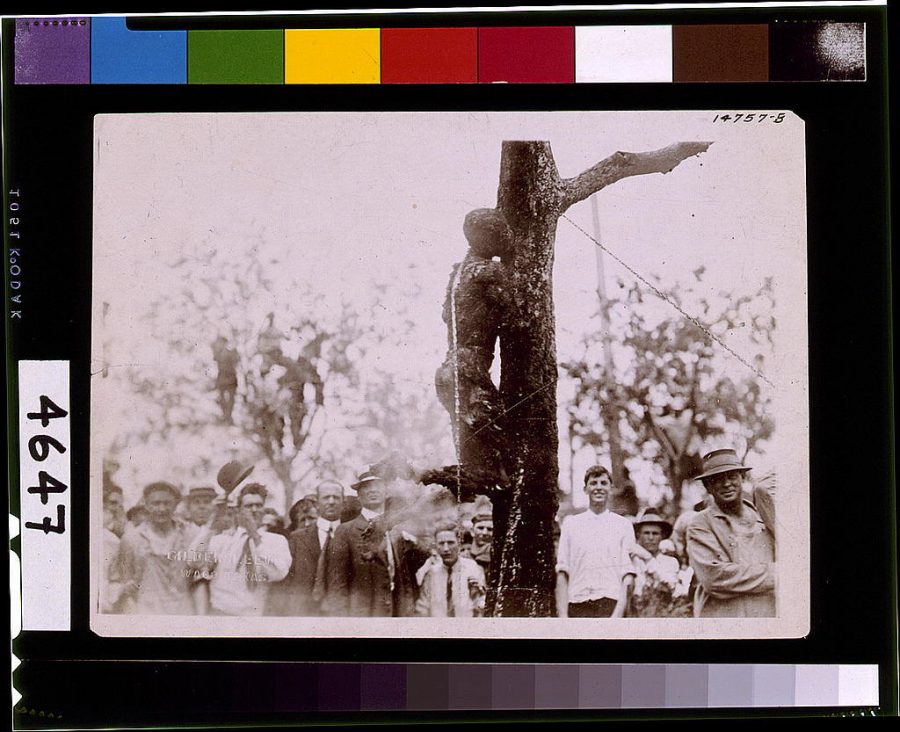

Lynching was a common occurrence, and many a Black man burned as this one did. Only difference is the Walkers were burned in their own home.

Untold Stories: The Lynching of the Walker Family

The untold story of the Walker family's murder is one of many stories that America refuses to acknowledge. This Black History Month, we're going to talk about it.

The point of Black History Month has always been to not only celebrate our achievements but to remember.

The good, the bad, and the ugly.

There is much African American history that isn’t spoken about in the same way Martin Luther King, Jr. or Rosa Parks are. The best parts of our history are spotlighted every year, but what about the bad parts?

What about the massacre of Black Wall Street (the Tulsa Race Massacre), the Ocoee Massacre, or Bloody Sunday?

In the same way, this country takes the time to constantly educate us on the Holocaust, it needs to acknowledge the darkness of its own history, particularly in regards to African American history.

We remember history in order for it not to repeat itself, no?

The bad in our history has just as much right to be remembered as the good, so for this Black History Month, I’d like to acknowledge the untold story of the Lynching of David Walker and his family.

May they rest in power.

The Nightriders formed in 1908, consisting of white yeomen farmers and fishermen in Fulton County, Kentucky, and Lake and Obion counties in neighboring western Tennessee.

Their goal was to oppose the West Tennessee Land Company, a group of private investors who had plans to drain the recently acquired Reelfoot Lake for cotton cultivation—the same lake used for both fishing and farming by local people.

Months went by of threats, beatings, and lynching other locals, with these same acts of violence quickly extending to the African American population to drive them out of the area.

Keep in mind this is also during a period when the expansion of the cotton economy into this area was being resisted because yeomen farmers dominated it. Cotton would mean slaves, and therefore African Americans—so how logical that locals took their anger out on the ones directly in front of them.

By the early 20th century, some African Americans in Fulton County had become landowners.

David Walker was among them, owning a 21 1/2-acre farm with a large cabin house where he and his wife were raising a family.

There were seven of them, dead by the end of the night.

Following an altercation Walker had with a white man, 50 Night Walkers showed up at his house in the night and threatened him, demanding he go with them. Naturally, the farmer and family man refused to leave his house.

In response, the mob poured coal oil on it and set it ablaze.

Walker pleaded for mercy on his family’s life and stepped outside, but was met with countless bullets with no hesitation.

His wife, with their infant in her arms, was met with the same fate.

“She held in her arms their infant child and begged the Night Riders for mercy. Disregarding her pleadings the infuriated mob opened fire and a bullet pierced the body of an infant in its mother’s arms. A second shot struck the mother in the abdomen and she fell, still holding the dead body of her infant.”(source below)

Three children were the next to die, quickly shot by the mob upon their exit of the house.

Only Walker’s eldest son refused to leave the cabin and died in there. As reported by the Courier-Journal:

“There is hardly a doubt but the oldest son of Walker preferred death by burning rather than to placing himself as the mercy of the mob, and it is probable that his charred body will be found among the debris.”

The local papers blamed Walker, with the Night Walkers claiming he swore at a white woman, which was a violation of Jim Crow custom. They claimed he had a bad reputation, and described him as a “surly negro.”

His land was taken over by his white neighbor, who later sold it to another white man.

Despite the governor condemning the situation and claiming he had a reward for any information given about the killings, no one was ever prosecuted.

Of course.

There are many other stories like this, ranging from individuals to families to entire blocks. Never forget, the bad is just as important.

Source: Wright, George C. Racial Violence in Kentucky, 1865-1940: Lynchings, Mob Rule, and "Legal Lynchings",

University of Illinois Press, 1990, pp. 123-124